How plastic is turning the Mediterranean into the most polluted sea in the world

It’s 6:30 on a sunny Tuesday morning in late April. Like every day, David is already aboard his Flequer and is waiting for me in his rubber boots and sun-bleached brown wool sweater. “Get on board and be careful not to slip, we’ll be leaving in a few minutes.”

The boat is small and there is barely room for two people. In the bow are the boxes to store the fish, in the stern the fishing net that David is untangling and that he will have to place once the other one has been recovered. “David, what does Flequer mean?” I ask him. “It means baker in Catalan. I didn’t give it this name, It already had it, but I haven’t changed it because it brings bad luck”. We set sail.

We only need a few minutes of navigation to reach the buoy that marks the point where begins the net that he had placed the day before. After about an hour and a half, the net and the day’s catch are on board the ship. In the time that David has taken to catch 12 kg of fish, 85 tons of plastic will have already ended up in the Mediterranean, the equivalent of 3 million bottles. I don’t think he knows this data, but I understand from his eyes and his words that he well knows the consequences. “Economically, this situation is ruin.” Fishing, he tells me, is increasingly scarce because pollution has destroyed the atrophic chain and production has decreased by 70/80% in the last 10 years. “We used to fish a lot of octopus between Badalona and Barcelona. Now there are no octopuses” because the contamination of the seabed has made the crab, its main food, disappear, “The seabed is dead”.

In fact, almost all of the 1.2 million tons of plastic estimated to be present in the Mediterranean are found at the bottom of the sea. Every year, according to numerous scientific studies, between 260 and 500 thousand tons of plastic are dumped into the water and according to the last reports by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), 99% of this plastic accumulates, in the form of microplastic, in marine sediments, while the rest is distributed between the coast, the sea surface and marine organisms. The Mediterranean, this small semi-enclosed sea, which represents only 1% of the earth’s water, is increasingly becoming a marine dump and is considered one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world and the most affected in terms of plastic pollution.

When we return to the port I meet Alfredo, a former fisherman friend of David. Alfredo helps us tie up the boat and unload the little box with the fish, looking at it with a bitter laugh. Seeing them together they seem like two opposite poles: Alfredo has a face hollowed out by the sun, a deep voice due to the cigarettes that always hang from his lips and a rather gruff look; David, on the other hand, is a calm man, with a round face and a melancholy gaze that conveys a feeling of pride mixed with the resignation of being one of the last. In the port of Badalona there are only 5 boats left and when he and the few remaining fishermen retire, artisanal fishing will disappear forever. Alfredo, who was a shellfish fisherman, already retired a few years ago because, he tells me, it was no longer worth it: “In recent years, shrimp, clams, snails and sole have disappeared. Luckily I’ve retired because it’s a shame what they’re doing”.

A growing number of studies have confirmed a particularly worrying concentration of microplastics and nanoplastics in marine environments and from there to our food. In a can of sardines, for example, materials such as polypropylene, polyethylene, phthalocyanine, and titanium dioxide have been identified (Karami et al., Science of the total environment 612,1380 (2018)). The effects of these substances on humans are still being studied, but given the importance of this problem, more and more scientists are investigating the subject. Characterizing these micro and nanoplastics is a particularly complicated operation and requires a combination of microscopy and spectroscopy. Images, as detailed as those produced by the ICFO institute in Castelldefels, are being analyzed to investigate the effects of these nanoplastics on living beings. The danger of these elements has been demonstrated in experiments with mice and fish and it has been seen that these particles are capable of accumulating in the tissues (liver, kidneys and intestines) and causing significant effects on the activity and health of the animals.

When we talk about these problems, we tend to think that they do not concern us directly, that they are problems that are far from us. But we should consider another fact: Spain is the European nation with the most plastic accumulated along the coast and the coastal areas surrounding Barcelona, with 26.1 kg per km of daily accumulation of plastic waste, represent the area with the highest coastal pollution at European level, the second in the Mediterranean only after the coast of Cilicia in Turkey. These materials are incredibly long-lived (it takes between 150 and 1,000 years for plastic to degrade) so virtually all plastic produced in human history is still present in the environment in some form.

This situation is the result of poor management throughout the life cycle of plastic, from production to consumption, to waste management and recycling of this material.

Production and consumption

The Mediterranean area is the fourth region in the world in the production of plastics. This production is largely driven by the demand for single-use items. More than half of this plastic becomes waste less than a year after it is produced, and most of it is sent to landfills or incinerators, rather than being recycled or reused.

Tourism

The Mediterranean is one of the regions with the greatest tourist vocation in Europe. The more than 200 million tourists who visit its coasts during the summer cause the amount of waste produced to increase significantly, often putting local waste management systems in crisis. As a result, marine litter increases by up to 40% during the tourist season.

Poor waste and collection management

Only 72% of the 24 million tons of waste produced annually is properly managed and ends up in controlled dumps. Most Mediterranean countries, however, still have too low levels of plastic collection and this means that 3.6 million tons of plastic, equivalent to 15%, are not collected and may end up in nature. This is the result of insufficient waste management capacity and uncontrolled or illegal dumping, mainly in the southern Mediterranean and the Balkans.

Little recycling

Few countries have achieved significant rates of separate collection of plastics, which would ensure a constant supply for recycling. Only 16% of the plastic produced is recycled. This is also due to low profitability in the recycling sector and the secondary market. In fact, in Europe, the operating cost to recycle plastic is estimated at €924 per tonne, which is significantly higher than the average selling price of secondary plastic, €540 per tonne. Recycling, therefore, remains unprofitable and it is much cheaper for companies to produce new plastic than to commit to reducing existing plastic.

The CRAM at Prat de Llobregat is one of the European reference centers for the protection of the marine environment and the species that inhabit it. In its 25 years of activity, it has welcomed, cared for and released hundreds of turtles, dolphins and seabirds. Here I meet Lucía Garrido, a veterinarian at the center and author of a study on the presence of plastic in the feces of sea turtles. When I arrive they warn me that it will be a “very full day”: the program foresees: transfer and test Massa Gran – a 137 kg tortoise, the largest in the center -, feed the two new tortoises just arrived at the center, medicate a small turtle with a wound in the shell and sacrifice a seagull that unfortunately cannot be saved. Lucía coordinates the volunteers with determination: she explains to them what they must do in a kind but resolute manner because, for the health of the animals, there is no time to lose. In a few hours, all the urgent activities have been completed and calm returns to the center. I meet Lucia while she is at the computer, busy writing the report on the morning’s activities. Her face looks a bit tired, she drinks an Aquarius and her blue uniform is now stained with turtle droppings. “During the year 2020, 51 Caretta caretta turtles have been treated at the CRAM and in 78% of the samples analyzed we found the presence of plastic.” This data -she explains to me- refers only to plastic visible to the naked eye; considering microplastics the percentage would be even higher.

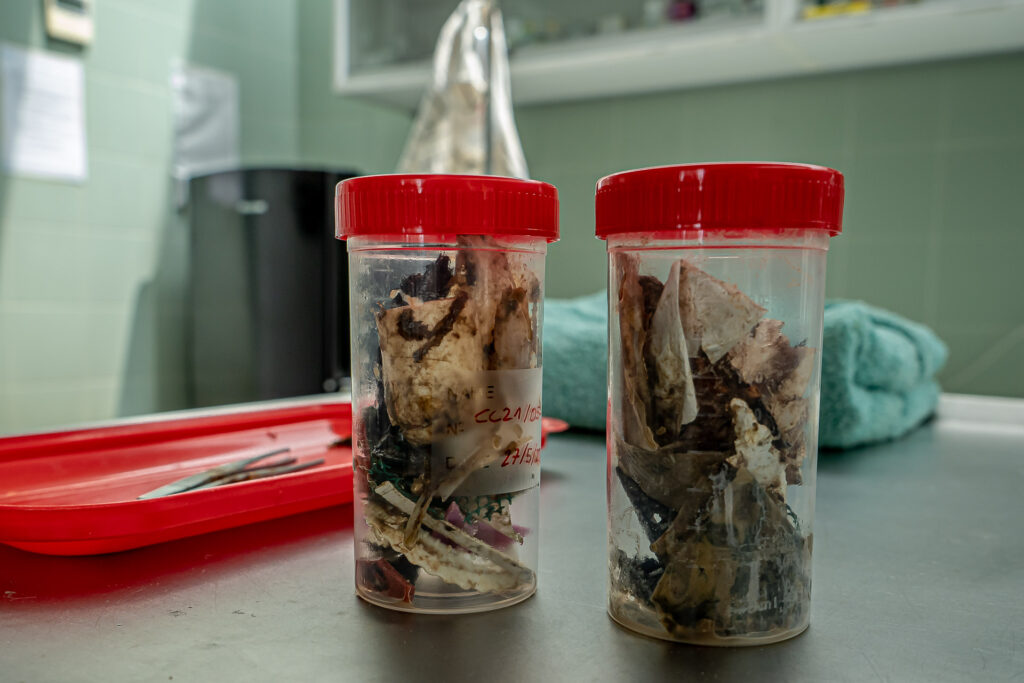

In all the necropsies carried out last year were found plastic residues: “These jars belong to an apparently healthy adult female who died of decompression syndrome. Her entire digestive tract was full of plastic.” Although plastic ingestion is not usually the main cause of death in turtles as it is in cetaceans, in several cases can occur enteritis that causes pain, anorexia and severely compromises the animal’s immune system. These data are particularly alarming because sea turtles are a good bioindicator of the state of pollution in the seas, since they tend to ingest plastic, have a wide spatial distribution and use all marine spaces, from the bottom of the sea to the surface. According to several reports, all species of sea turtles, approximately half of the species of mammals and one fifth of the species of seabirds suffer a direct impact related to marine litter, not forgetting also fish and invertebrates (Cole et al ., 2013; Schuyler et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2014; Nelms et al. 2015).

“The number of species known to be affected by plastic, especially due to ingestion, is increasing alarmingly as studies on the subject increase.” One of these studies is the one coordinated and directed by Miquel Ventura, a marine biologist member of the RAED – Royal European Academy of Doctors, and the promoter of the Silmar project. For more than 3 years, with its biological stations distributed throughout different points of the Catalan coast, it has been studying the state of health of marine biodiversity, recording the evolution of the situation in its annual report. The Mar Bella beach station in Barcelona -he tells me- is an ideal place to monitor the changes in the ecosystem due to our daily activity, associated with hyper-consumption and the intensive use of natural resources, which lead to serious environmental problems with negative effects for our lives and for nature. The study on biodiversity at this station last year highlighted, among other data, “a low percentage of sessile filter-feeding species that gives us an idea that the area has high water turbidity that hinders the development of this type of marine organism.”

Coastal cities like Barcelona are under high pressure due to population growth, mass tourism and the dynamics of large commercial companies. “These factors contribute to a complex situation regarding waste management, aggravated by insufficient planning and sanitation infrastructures, common factors in the world’s large cities and especially in developing countries. The management and treatment of waste in coastal municipalities must be reconsidered to adopt more sustainable and efficient innovative alternatives”. Today, the highest priority is focused on developing the capacity for effective management of plastic waste to give value to the by-product, revalue it and prevent its introduction into the sea to lower dramatic data such as those from the Barcelona Institute of Marine Sciences according to which in Barcelona sees an average of 290 kg of waste per km². The plastic waste present in nature with time will break down into smaller pieces, becoming microplastics that integrate into the environment.

To talk about this topic, I meet Sara Higueras, a collaborator of the Surfrider Foundation Europe, and coordinator in Barcelona of Surfing for Science, a project that aims to evaluate microplastic contamination in the coastal zone with the collaboration of citizens who collect scientific samples by paddle surfing. “With this project we want to quantify the plastic in the area closest to the bathing zone because before the studies were being done with oceanographic vessels or big boats that could not get close to the beach, which is the place where the plastic really affects more to users. With paddle surfing it is possible to collect samples in the coastal area.” The “manta”, a funnel-shaped floating net, is tied to the paddle surf and all the microplastic fragments found on the surface are captured in its tiny meshes. These fragments are then collected and analyzed in the laboratories of the University of Barcelona to quantify their presence and identify their origin, so that actions can then be taken to try to improve the situation. “If we find a high presence of hygiene products, we must invest more efforts in the purification of wastewater; if we find pellets, we can identify the companies responsible for these leaks; if we find remains of artificial turf, we can design mechanisms to ensure that rainwater from soccer fields passes through a treatment plant first”.

This project demonstrates a desire for change on the part of civil society, which in many cases has become aware of the problem and is trying to mitigate the harmful effects of plastic pollution. There are more and more initiatives of this type, such as beach cleaning activities that are organized weekly, diving center initiatives for underwater cleaning of plastic waste or abandoned fishing nets, or educational initiatives for new generations. However, these actions, although important and laudable, by themselves are not enough and cannot be effective without a strong commitment at the political level and a change in our consumption model.

According to the IUCN report, “The Mediterranean: mare plasticum”, current measures are not significantly reducing plastic leakage into the Mediterranean and, without radical intervention, this amount is expected to double in the next 20 years. The main actions that could help reverse this trend are related to improving waste management systems, banning plastic bags and improving recycling efficiency in the 100 most polluting cities in the Mediterranean. Other important actions, according to WWF’s “Stop the Plastic Flood” are:

- the European extension of the EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility), a scheme to encourage the adoption of more recyclable products that establish that producers pay a contribution for the plastic materials produced,

- the ban on the production of disposable plastic items and personal cosmetics, soaps and detergents containing microplastics,

- increasing the collection and separation of recyclable materials,

- improving waste management capacity with more controls and economic sanctions for countries that do not close illegal dumps and increased investment in recycling programs instead of creating new dumps,

- investment in more recyclable materials in order to generate a stable demand for recycled products, to make this practice profitable and create a circular economy.

However, at the base of all this, one of the fundamental factors to be taken into account is not of a technical or economic nature but of a social nature and consists of improving the education and environmental awareness of all citizens and creating the conditions so that new generations are aware of the problem and do not repeat the mistakes of the past.